Cross-hatching

Land inhabited by people ages like skin. New lines form, cross-hatching the old. Time alone is a sufficient condition.

For most of the 18th century, the area of Marlborough Point and Potomac Creek was the heart of activity in Stafford County. Attempts by colonial authorities and investors to create a lasting township failed to take root, however, and the area lost its economic importance.(1) Decades later, the 1860 census – on the eve of the Civil War – recorded a County population of only 8,633. About thirty-nine per cent of Staffordians were Black, the great majority of whom were enslaved.

|

| The "Beanpoles and Cornstalks" Potomac Creek bridge that a nervous Lincoln walked across in 1862. (Source: Stafford County Museum) |

Wartime occupations by the 135,000 soldiers of the Union Army of the Potomac and far smaller Confederate forces left behind a deforested landscape and induced waves of migration. Encouraged by the federal presence, 12,000 enslaved Blacks escaped north through Stafford County. Many crossed Potomac Creek to do so. After the war, Northern-led Reconstruction offered little room for optimism for White families. Their laborers gone and exposed topsoil washing away, many left Stafford, often bound for Kentucky where Southern sentiment remained strong. Historian Eby describes a post-war County with a small, dispirited population and an economy that would not recover until the 1970s.(2)

|

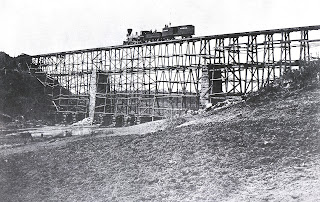

| The sturdier 1863 bridge that replaced the earlier one. (Source: Stafford County Museum) |

Today, it’s possible that a few of Stafford’s very oldest residents may also recall being relocated by war. Marine Corps Base Quantico displaced locals in 1942 to occupy 30,000 acres – almost a quarter of the County. Three hundred fifty families had to leave on short notice, twenty to sixty days, their land condemned by the federal government.

***

But what’s happened since was probably unthinkable to most residents in 1942. Stafford is now in one of the fastest growing areas in the country. Its current population of 160,000 is four times what it was in 1980 (it was less than 25,000 when our family moved here 50 years ago). As the federal government continued to swell, the I-95 interstate highway bisected the County in the 1950s, paralleling old and tedious Route 1, a dirt road paved earlier in the century. A new commuter rail line tied Stafford to Washington DC in the 1990s. These novel pathways reset the flow of people and goods along a north-south axis, away from the natural, mostly east-west passages long mandated by local rivers and creeks. New families in need of homes rushed in. The part of I-95 running through Stafford is now absurdly congested, often called the worst traffic “hotspot” in the nation.

|

| Traffic in Stafford (Source: The Free-Lance Star) |

It’s a disorienting place to live. And big changes have influenced residents’ sense of place. As happened after the Civil War, and after Captain John Smith’s visit in 1608, and doubtless many times before Europeans ever walked here, Stafford County is once more a place of been heres and come heres.

Not long ago, an elderly woman told me that she knows people who are waiting for her to die so her land can come to market, perhaps to be occupied by a stranger. How many residents of the Creek have held such knowledge, have felt that incoming presence? The land itself is a palimpsest of peoples.

Comments

Post a Comment