The English Tradition

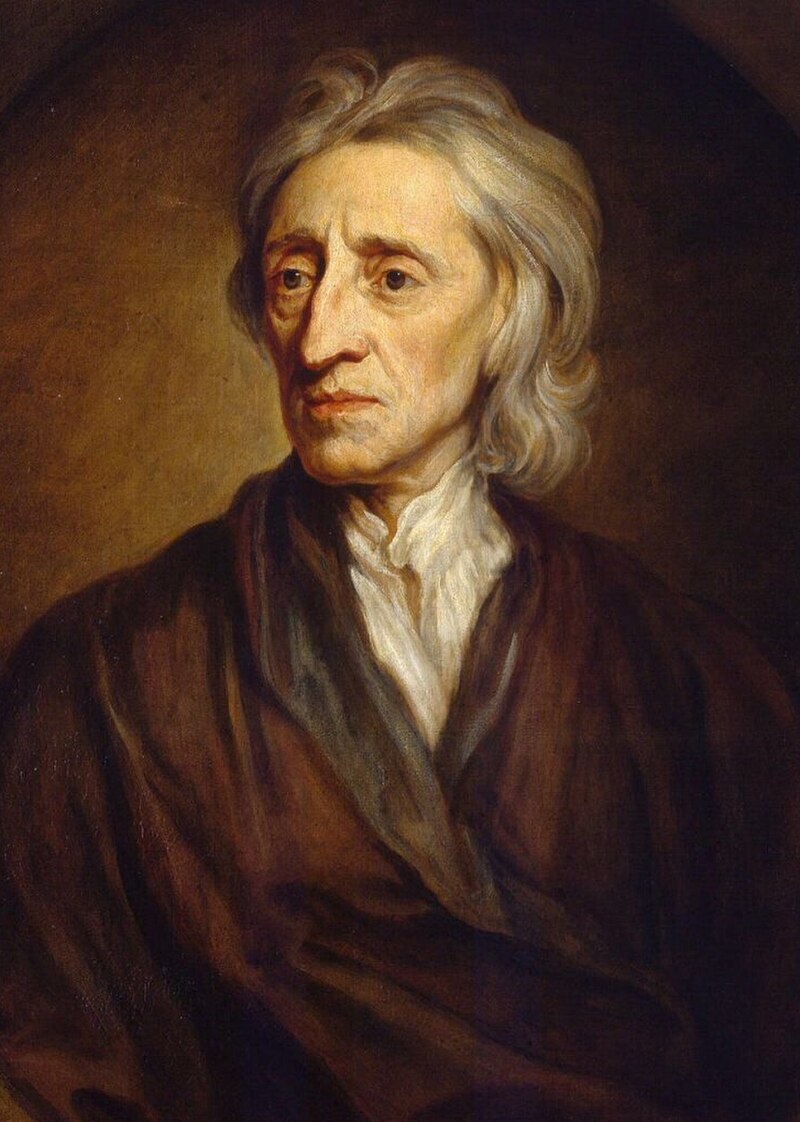

Potomac Creek runs through Stafford County, and whether their ancestors arrived from the British Isles, as Hessians during the Revolutionary War, or otherwise, County been heres tend to think about land in the English tradition. To be successful is to own your own land. More importantly, to have kept it over time is to have earned it through generations of hard work without which, as seventeenth century English philosopher John Locke wrote, “it would scarcely be worth anything.”

|

| John Locke 1632-1704 (Wikipedia) |

According to Locke, human labor “puts the difference of value in everything.” This is especially so with land:

[L]et anyone consider what the difference is between an acre of land planted with tobacco or sugar, sown with wheat or barley; and an acre of the same land lying in common, without any husbandry upon it, and he will find that the improvement of labor makes the far greater part of the value.[1]

It's hard to exaggerate the impact of this straightforward idea, known as the labor theory of property. The “Father of Liberalism,” Locke was essential reading for the leaders of the American Revolution. His theory also informed the Homestead Acts that gave western land to settlers willing to work it, and provided the basis for Karl Marx’s critique of capitalism. It is an ambitious theory suited to ambitious people. As proof of its validity, Locke pointed to America’s Indigenous peoples; like many Europeans, he erroneously believed Indians did not improve their land by labor. For this simple reason, he argued, even the “kings” among these native “Americans” were materially worse off than a common English day-laborer.

How is this relevant to modern Stafford County? Locke’s theory of property is part of the bedrock of County tradition and culture. Ideologically, it accomplishes several big tasks for long-time residents.

The first is that it prioritizes physically working

the land. Dirt is dirt, but – if you’re open to it – the practice of working one’s

own land may create a distinct consciousness, a notion of being rooted in place.

You hear many echoes of this in Stafford, especially from been heres: “We spend a lot of money to fix this place up. We make

part of a living off it. That’s the difference between a farmer and landowner”;

“Being a farmer, you have a love for the land. You’re proud of it, and able to

keep it”; and so on.

Relatedly, for some belief in the labor theory of property also explains (and even justifies) why Indians lost their land: because they deserved to. Implicitly, land ownership becomes a meritocracy, a possession that comes to those worthy of it. If the land was important or sacred to Native Americans, why didn’t they do more with it? Or, as one landowner told me regarding a local tribe's protests over a new housing development, the slightly updated “Why didn’t they buy it?” -- as the ambitious developer had done.

|

| Potomac Creek |

Of course, the obvious question is how people of African descent came to be excluded from this logic. That they worked the land – albeit for the most part involuntarily – is inarguable. Nor was Locke himself a great fan of chattel slavery (the type that makes people the property of others). [2] And the White American revolutionaries who decried English tradition in the eighteenth century did so because they believed it infringed upon their natural rights as individuals.[3] They sought liberating change, not continuity. So, what gives? Why not extend the theory to those working the fields?

As Alan Taylor shows in his Pulitzer Prize-winning history of Virginia, in the revolutionary age enslaved Africans were feared for their large numbers and their own rebellious potential. They were also strongly – and positively – tied in landowners’ minds to aggressive new ideas about the profitable management of estates. The problem for White colonial landowners was how to transform enslaved persons into a form of liquid capital. They wanted to be able profitably to sell or divide their property, including people. Yet old laws of entail and primogeniture kept estates intact, and had long bound laborers to landed estates. Breaking these ties between enslaved workers and the land would make the former more economically useful.

And that’s what the revolutionary landowners did. The Virginia legislature abolished entails in 1776 (over the objections of the colony’s royal governor) and primogeniture in 1785. The effect was immediate. As soon as the 1780s, Taylor writes, “40 percent of slaves advertised in the Virginia press had been sold at least once before in their lives: up from 24 percent in the 1760s.”[4]

In short, Locke’s theory tying land labor to land ownership was potentially liberating – but for the wrong people, in the White slave owner’s view. Africans – as property – differed in colonists’ minds from Native Americans. On this subject, Liberal Thomas Jefferson, the gifted, property-conscious Virginia native, the drafter of the Declaration of Independence, and the mass enslaver, retreated from talk of universal human rights into “a biological mandate for inequality.”[5] For most Virginians, the status of Africans simply was too deep a river to ford.

The final big task accomplished by belief in Locke’s theory that labor gives land its value is that it sanctifies current ownership of private land. To defend existing land rights, such as the near-sacred principle of "by-right" development, is therefore to honor the work of (implicitly) deserving ancestors.

This valuation is what less-established County come heres may find hardest to grasp. By definition the leavers of places, they seldom share this heritage, and just aren’t as taken up by the fullness and psychic gravity of possessing and working private land. That elemental passion is what’s being lost today in Stafford. The earth literally moves as each year thousands of come heres settle into three-acre lots or rent townhouses with blue vinyl siding. What most excites Potomac Creek’s newest residents is good shopping, ball fields, and public land for nature hikes, not bailing hay in your grandfather’s field.

For briefs on primogeniture and entail (and how they affect the plot of Downtown Abbey) look here.

[1] John Locke, The Second Treatise of Government. (c. 1681). In David Wootton, ed. John Locke: Political Writings. (Penguin: 1993). 281.

.jpg)

Comments

Post a Comment